Monday, 26 September 2011

Time For QE2?

Sunday, 25 September 2011

Not Quite The Whole Truth

£1.75 trillion deal to save the euro - Telegraph

Tuesday, 8 February 2011

British Banks–The Gift That Keeps On Giving

The news that Mr Osborne intends to make the bank levy more stringent than originally planned. Needless to say, the apologists from the financial economy are crying ‘foul’ and warning of a mass exodus from these shores. The trouble is that they did exactly the same last year – with the introduction of the one off tax on bank bonuses – and here they are again, still trading in London.

Two aspects of the proposals need highlighting. First, there is a view prevalent in the country at the moment that whilst the banks caused the mess that all of the taxpayers are having to clear up, the banks are not enduring a fair share of the pain. At a time when libraries are closing, essential social services are being cut back, and education spending is being reduced, we are also seeing the prospect of record profits in the banking sector and a return to stellar bank bonuses. The banks will gain little sympathy beyond the circle of sycophants over these proposals. Many will feel that they may not go far enough.

Second, there is the question of how the economy should be balanced in the future. Many question the wisdom of returning to an economy that is top heavy in the financial economy. A reduction in the reliance upon the banking sector would actually make the economy a bit more resilient to the shocks within the global economy. Those of that view point to Germany as an example of a balanced economy that has weathered the recession quite well. This addresses the issue of bank exile. If the risky, toxic, bank operations were to be driven away from the UK – say to New York or Hong Kong – would it be such a bad thing?

To me, this seems like something of a turning point. Until now, Mr Osborne had appeared to have been a captive of the banking fraternity and the financial economy. Only recently did he say that the ‘Banker Bashing’ had gone too far. Now he is bashing banks himself. Does this represent a major change in policy? Does he realise that for his gamble to pay off, he needs to rebalance the economy away from financial services and towards manufacturing exports? Let’s hope so!

© The European Futures Observatory 2011

Increased bank tax to raise £2.5bn - UK Politics, UK - The Independent

George Osborne levy attacked by banks and Ed Balls - Telegraph

Wednesday, 2 February 2011

Can Interest Rates Control Inflation?

As the titanic struggle between the real economy and the financial economy intensifies, the question has arisen about using interest rates as a tool to reduce the current bout of inflation. We have argued that they would be rather a bunt instrument simply because they would address the symptom and not the cause of the disease. The current bout of inflation is the result of the rising world price of commodities. This has mainly been caused by the recovery of the Icarus Economies in Asia, it is a demand led inflation.

Raising interest rates work by dampening demand to such a point that, as sales fall, companies respond by cutting their prices (or, at least, not raising them as fast). Demand is reduced by taking money out of the economy. That money doesn’t disappear though. Instead, it acts as a wealth transfer out of the real economy and into the financial economy. No wonder that it is the banks and financial institutions who are leading the charge for higher interest rates.

Which leads us back to the politics of the current situation. For Mr Osborne’s Gamble to pay off he needs the real economy to deliver growth through investment and exports. These are not helped by higher interest rates. Which creates a dilemma. In order to collect from his gamble, Mr Osborne has to turn his back on his natural constituency in the City.

We live in interesting times!

© The European Futures Observatory 2011

FT.com / Comment / Letters - Raising interest rates is a poor tool to fight inflation

Sunday, 16 January 2011

Business As Usual?

One of our contentions is that the financial economy and the real economy each run to a different rhythm. At times when both of the economies are synchronised, tremendous gains are made. When they are out of step, then problems arise. Our current economic difficulties originated in a hic-cup in the financial economy. There was an edifice of credit given too easily to people who were patently unable to repay the loans (what Will Hutton calls the ‘Ponzi Economy’), regulators who were unwilling to regulate this lending, and a financial sector driven by greed and personal enrichment to expand this lending beyond safe limits. All of this came tumbling down when the financial economy hit a speed bump.

It was by no means certain that the contagion in the financial economy would need to spread into the real economy. After all, the bursting of the ‘Dot.com Bubble’ only had mildly recessional implications. However, a combination of a poor and tardy policy response – particularly in the US – allowed the contagion to bleed from the financial economy into the real economy. And here we are, where we are – the worst recession since the 1930s.

The financial economy and the real economy are still out of step. Across the OECD, unemployment remains high, there is still a relatively large debt overhang in the public and household sectors, and the output gap remains higher than previously experienced. All of this suggests that the real economy needs further fiscal and monetary stimulation. The financial economy, on the other hand, has largely recovered from where it was during the credit crunch. Credit is flowing again - albeit at much reduced trading volumes - the financial system has been shored up, bank profits have returned, and even large bonuses are back on the agenda of bankers. The danger, as the financiers see it, is the nascent inflation that could result from the recent monetary expansion. The financial economy needs interest rates to be increased as part of a monetary contraction.

In many respects, this reflects a desire to return to ‘business as usual’. Of course, if I were an investment banker, I would see the logic behind returning to stellar salaries as quickly as possible. However, the policy of ‘business as usual’ implies that we continue to make the mistakes that put us into recession to begin with. This suggests that the financial economy has yet to come to terms with the paradigm shift that the recession has caused.

For example, the conventional wisdom that proved to be unwise in 2008 states that if inflation is building, then interest rates should be increased and monetary policy should be contracted. If the MPC were to follow the suggestion of Andrew Sentance to increase interest rates, would it work? We think not. The main inflationary pressures that we are currently experiencing are structural in nature caused by rising food, energy, and commodity prices. Raising interest rates may cause Sterling to appreciate a little (or it may not), taking the pressure off those food, energy, and commodity prices denominated in US Dollars, but the impact on global food, energy, and commodity prices is likely to be negligible. UK interest rates would have to rise very far in order to have an impact on global commodity prices.

Instead, such a policy is likely to do severe damage the real economy. Low inflation rates and a low value of Sterling, which fell by between 20% to 25% in the period 2007-10, have stimulated the UK manufacturing sector that exports to Europe, the US, the Middle East, and the Far East – i.e. those economies based around the Euro and the US Dollar. Whilst the cost of imported materials have risen, this is unlikely to lead to a domestic inflationary spiral because of the sheer size of the output gap. There is too much slack in the economy, particularly with the public sector redundancies starting later this year, for inflation to get out of hand.

And this is the point at which we arrive. If it is UK policy to nurture the exporting manufacturing sector, then interest rates need to be held low for some time to come, despite the occurrence of structural inflation. If, on the other hand, interest rates are raised, then it signals a surrender to the financial economy and a return to ‘business as usual’.

If this occurs, the we ought not to complain too much about bankers bonuses. After all, that is part and parcel of our economic policy.

© The European Futures Observatory 2011

Friday, 29 October 2010

Anyone For Tea?

The forthcoming mid-term elections have taken on the hue of a referendum on the popularity of President Obama. A mere two years ago, the President was billed as a new and dynamic political force in America. His rally cry was ‘Hope’, his exhortation ‘Yes, we can.’ And yet, the programme seems to have come off the boil. ‘Hope’ now turns out to be ‘Hype’ and, in an unguarded moment on a TV show recently, he now says ‘Yes, we can. But, …’ If the polls are anywhere near to being correct, the President’s party is facing a substantial defeat in the voting next week. As an outsider looking in, I am interested in why America has fallen out of love with Obama? Why is it that his opponents are so hostile towards him? What exactly is driving the extreme views of the Tea Party opponents to the President?

I guess that the single word answer is ‘recession’. America is experiencing a recession that is at the worse end of the OECD experience, and this is exposing some of the fractures within American society. However, we like to take a longer view of these fractures in seeking an explanation.

According to Edward Luce of the FT, “the annual incomes of the bottom 90 per cent of US families have been essentially flat since 1973 – having risen by only 10 per cent in real terms over the past 37 years”. This is quite an interesting statistic because it also explains so much. If income has flatlined in this period, and living standards have been increasing, then how has the American Dream been paid for? By an increase in household debt. It would appear that American consumers have been borrowing to improve their living standards. A good part of this increase in debt was underwritten by a boom in the housing market, as households used their mortgages as credit cards.

Of course, there is nothing inherently unstable about this money-go-round until the music stops. Once that occurs, then everyone wants to ditch the parcel rather than being left with a dud asset. As the credit crunch – essentially a financial phenomenon – bled into the real economy, the resulting recession has had two important consequences. First, there is an acute shortage of credit to finance further expansion of consumer expenditure (more on this later), and second, there arises unemployment at sufficient volumes that the servicing of existing debt is called into question.

This is compounded by the composition of the borrowers. Many of those who have borrowed to finance their lifestyles are of the Boomer generation, and one thing that characterises the Boomers is their deep sense of entitlement. We now have a situation where a generational cohort, who are accustomed to being treated like spoilt children, have had their toys taken away from them. They are angry. They are angry enough to form Tea Party groups. They are angry enough to call into question whether their own President is American. They are angry enough to give credence to extremists such as Glenn Beck. And they may just be angry enough to vote into office someone like Christine O’Donnell, who is manifestly unfit for office.

It could be quite easy for Europeans to become smug over the discomfort of America. However, just an element of deep thought stops this train of thought. It is the angry, white, lower middle class who are giving electoral backing to the Neo-Nazi parties in the UK. It is the respectable burghers who are giving electoral support to the anti-Islamic parties in the Netherlands. It is the middle class establishment who are behind the hounding of the Roma in France and Italy. There are angry middle class voters across the developed world at the moment.

This is likely to be a feature of our near future. If recovery is sluggish (the best case scenario) or if recession makes a re-appearance (the worst case scenario), it is unlikely that middle class household balance sheets will be repaired quickly. In the past, the world has waited for American households to start borrowing to finance their consumption, thus kick-starting the world economy. This is unlikely to happen for some time – American households are simply too maxed out. This suggests that middle class anger will remain for some time to come, which will make our politics just a little more xenophobic and our economies just a little less globalised.

We call this trend the ‘New Nationalism’.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

FT.com / Reportage - The crisis of middle-class America

On the Way Down: The Erosion of America's Middle Class - SPIEGEL ONLINE

BBC News - Number of Americans living in poverty 'increases by 4m'

Glenn Beck Leads Religious Rally at Lincoln Memorial - NYTimes.com

BBC News - Profile: Christine O'Donnell, Delaware Senate candidate

Growing Number of Americans Say Obama is a Muslim: Pew Research Center

Thursday, 28 October 2010

Ageing Europe

BBC News - Q&A: French strikes over pension reforms

Wednesday, 27 October 2010

Ever Increasing Union

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Bush III

BBC News - Canadian militant pleads guilty at Guantanamo tribunal

Monday, 25 October 2010

Productivity–vs- Competency

BBC News - Tetraplegic man's life support 'turned off by mistake'

Sunday, 24 October 2010

Globalisation Fast Tracked

Saturday, 23 October 2010

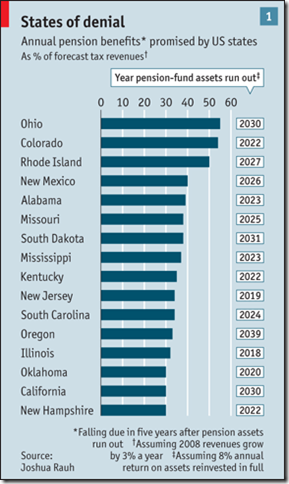

When The Well Runs Dry

Of course, the bond markets will intervene well before this scenario occurs, but it does suggest that, towards the end of this decade, a crisis in State funding – along the lines of the crisis in the Eurozone – will befall the Dollar.

Ooops … it looks as if we can’t afford to retire!

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Thursday, 21 October 2010

QE2?

QE is also being used to fine tune the economy. I rather suapect this to be something of a blunt instrument. The policy of fiscal tightening and monetary loosening is novel, but I do fear that the tightening might be overdone. For example, for Mr Osborne's plans to work, the private sector needs to generate something like a million jobs in the next four years in order to soak up that half million recently unemployed during the recession and the half million displaced public sector workers created in the recent spending review. This seems like a tall order at a time when GDP growth will be, at best, muted. A million jobs over the decade might be a more reasonable prospect.

Which brings us to Faisal Islam. His article for Prospect Magazine rather reflects conventional thinking. Stuck in the grip of a neo-classical base for his economics, he fails to grasp the key points of QE. In my view, this reflects the failure of economics more than anything else. Perhaps what we need is a new economics?

The Great Money Mystery – Prospect Magazine « Prospect Magazine

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Wednesday, 20 October 2010

US inquiry into China rare earth shipments

BBC News - US inquiry into China rare earth shipments

© The European Futures Observatory 2010