BBC News - EU to target private lenders in future bail-outs

Monday, 13 December 2010

Spooking The Horses

BBC News - EU to target private lenders in future bail-outs

Saturday, 11 December 2010

The Geopolitics Of Scarcity

BBC News - China sees inflation jump to 5.1%, a 28-month high

BBC News - Chinese exports jump unexpectedly amid inflation fears

Saturday, 20 November 2010

Finding An Alternative

Friday, 19 November 2010

A Prelude To Scarcity

In recent days, there has been quite a lot of interest in the issue of long term scarcities. This is an area upon which we have been working for over a year now – longer if we include the work on the Post-Scarcity World – and it seems to be an area that is coming into fashion. The argument for scarcity is well rehearsed. In 2000 there were 6 billion souls on the planet. By 2050 the mid-estimate of the UN is that there will be 9 billion people. Balanced against this increase in potential demand for resources is the view that we are coming to the point of peak production for many resources, thus potentially restricting their supply. The result of this clash of rising demand against falling supply will be an ‘Age Of Scarcity’.

Of course, the transition to the Age Of Scarcity is not likely to be discontinuous. We are likely to drift into a position of scarcity over a number of years, with, every now and then, a prelude of what is to come. We would argue that this is what is happening with food prices. After a long period of falling food prices in real terms, from 1980 to about 2002, food prices appear to have started to rise on a long term trend. This trend, underpinned by growing demand in the emerging economies and by modest improvements in crop yields, looks set to continue for some time to come.

Every now and then, a combination of natural disasters, the impact of climate change, the impact of trade nationalism, and so on, serves to tighten the markets a bit. It happened in 2008, and is again happening in 2010. To this extent, we are witnessing over a small period of time what may well happen over a longer time frame. We are witnessing a prelude to scarcity.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

The Economist food-price index: Malthusian mouthfuls | The Economist

Thursday, 18 November 2010

How Rich Are The Poor?

My son is currently living in Taiwan, so stories about Taiwan naturally catch my attention at the moment. There was a story in The Economist about how Taiwan is on the verge of becoming richer than Japan. The counter-intuitive nature of that comment really did catch my attention.

The Economist is quoting IMF figures when it states that the GDP per head of Taiwan is set to be $34.7K this year, against $33.8K for Japan. However, once we start to drill into the figures a different picture emerges. The Dollars used are not real Dollars but ‘PPP Dollars’ (Purchasing Power Parity Dollars). PPP Dollars are an artificial construct that attempts to weight income in terms of the cost of living across countries. The Japanese figure is discounted more heavily than the Taiwanese figure because Japan has a much higher cost of living. However, the adjusted figures do suggest that Taiwan has a better standard of living than Japan, which fits in with the impression that my son creates.

Does this matter? In a sense it doesn’t. These figures a a bit arbitrary and the PPP weightings are something of a guesstimate rather than an accurate measurement. However, there are times when it is important. According to some measures, China will move from the third largest economy in the world to overtake Japan as the second largest economy in the world this year. What we lose in this statistic is exactly how poor China is. The ranking of number two is a volume effect (well over a billion Chinese citizens) rather than an income effect. According to the IMF again, but for 2009 instead of 2010, China ranks 99th for GDPO per head in PPP Dollars (Taiwan ranks 37th and Japan ranks 17th).

Which is the rich country and which is the poor? China could be seen as a rich nation – the second largest economy in the world – whilst at the same time being one of the poorest - 99th in terms of GDP per capita. We haven’t quite come to grips with this dichotomy as yet, and some would say that this will be one of the future challenges that we face.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Wednesday, 17 November 2010

The Luck Of The Irish

The case of Ireland and its present difficulties does pose a few questions that have a much longer perspective. If the Euro experiment were ever to work, then there would need to be a great degree of monetary co-ordination, along with a fair amount of fiscal co-ordination. The establishment of the ECB has, by and large, achieved monetary co-ordination. It was the role of the Stability and Growth Pact to harmonise fiscal policy by limiting budget deficits to 3% of GDP and public debt to 60% of GDP. The failure of the Stability and Growth Pact, almost from inception lies at the heart of Ireland’s present difficulties.

In recent years, Ireland has based its ‘Celtic Tiger’ credentials on a policy of the competitive reduction of Corporation Tax. Businesses, particularly UK businesses, have responded by relocating in the low tax environment. That now appears to have been something of a mistake. Now that the Irish bubble has burst, the nations bailing out Ireland – the victims of competitive tax policies – have a say in the future management of the Irish economy. Just as the Greek bailout is predicated by the reduction of public spending to more sustainable levels, so an Irish bailout is likely to be predicated by the raising of taxes to more sustainable levels.

This is of tremendous significance because it would imply the loss of Irish fiscal sovereignty. The Irish government has gambled on a low tax Tiger Economy and has lost and now it has to pay the price accordingly.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Hamish McRae: Sovereign defaults in the eurozone are inevitable

Friday, 5 November 2010

X Marks The Spot

When we last wrote about Mr Osborne’s Gamble (that fiscal tightening and monetary loosening will bring us out of recession), we left the issue of politics on one side. If the Gamble fails to work in an adequate time frame, we are unlikely to be able to leave politics out of the equation because this will be the arena in which the consequences of failure will be felt, as President Obama found to his cost this week. It is interesting that the political arena in the UK has experienced a significant long term change this year through the generational rebalancing of British politics.

Over the course of this year, Mr Brown has been replaced by Mr Miliband as leader of the Labour Party and Mr Clegg has moved from obscurity to Deputy Prime Minister on behalf of the Liberal Democrats. There has been no change in the leadership of the Conservative Party. The one thing that all of the current party leaders have in common is that they belong to Generation X, and that they have replaced Baby Boomers as party leaders. We have already felt some of the consequences of this, but far more are to come.

To recap on generations, the Baby Boomers in the UK represent a generational cohort that has almost been a golden generation. They grew up in the rising prosperity in the 1950s, they provided the flower power generation of the 1960s, they benefitted from the great housing inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, and they are currently starting to retire on gold plated pension schemes. They are self-absorbed, self-indulgent, and spoilt.

The children of the Boomers – Generation X – have experienced a different life pattern. They grew up in a world of strikes and three day weeks, of stagflation, of youth unemployment in the Thatcher years, and of a struggle to get onto the housing ladder. They are the original punk generation who have lived a life of low paid and insecure jobs, and who have learned to get by through making the best of a bad job. This ability to muddle through is what the Xers are bringing to the leadership roles into which they are now moving.

One of the great attributes of the Xers is their pragmatism, and this is starting to show though in politics. For example, the Liberal Democrats gave a clear promise in their manifesto not to increase VAT (a UK sales tax). Within weeks of attaining power, that undertaking had been abandoned because of expediency as part of a more general fiscal tightening. Again, each Lib-Dem MP signed a written pledge not to increase Student Tuition Fees. Again, within weeks of attaining power that pledge was abandoned in the name of fiscal pragmatism. The Boomers accuse the Xers of not keeping their word, which they haven’t. However, this does not prick the Xer conscience because the situation warranted this change of heart.

When we take this thinking to Mr Osborne’s Gamble, we can speculate that if the gamble doesn’t pay off, then the policy will be changed – in short order – to a policy that does work. The most likely candidate would be that the fiscal tightening will not be tightened as hard as originally planned. There are lots of areas in which the policy can be reversed. Many of the spending cuts will adversely affect the Boomers, who are now flowing into the ranks of the retired.

As these parts of the public sector are cut back, the Boomers will howl with rage like children who have had their toys taken from them. For example, there was an absolute furore when it was suggested that free bus passes for all retirees – irrespective of their wealth or income – be removed. The Boomer sense of entitlement was outraged at this suggestion, which was made in the cause of saving public spending. There is likely to be more of this in the near future, particularly as local government works out which areas of the public sector to retreat from. Politically, it would be tempting for an Xer Chancellor of the Exchequer to buy Boomer votes by not pruning so hard if the gamble fails to work as planned.

To our view, this gives shape to Plan B. Renewed Quantitative Easing will provide an early warning signal of the gamble not paying off. If things continue to worsen, then the pragmatic aspect of the present government is likely to come into play to allow for some fiscal easing as well, possibly by spending a bit more on the ageing Boomers.

In this respect, we are fortunate to be surrounded by pragmatic Xers because the last thing we need right now are doctrinaire politicians.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Thursday, 4 November 2010

The Pace Of Change

We live in a world that demands things to be done instantly. President Obama has just been punished for not taking the US economy out of the worst recession in recent history in less than two years. When I offer the opinion that the recovery could well take the rest of this decade, I am usually met with sheer disbelief. We want everything done now, and we expect that in others.

Of course, not all in the world march to that tune. The issue of political reform in China is one case in hand. There is much pressure from the west – principally the US, but also the European nations as well – for China to reform its political institutions. China replies that it is, but at a pace of gradual reform rather than at breakneck speed. Exactly how far things have moved can be seen in John Humphrys’ report for the BBC.

In a 30 year retrospective, Mr Humphrys reports on how much has been achieved in one generation. By comparison with 1980, China is a much more open, tolerant and pluralist society. By western standards there is still a long way to go, but perhaps the cause for political reform might be helped more by congratulating the Chinese government for what it has achieved rather than berating it for what it has yet to achieve?

Sometimes we should be a bit more tolerant ourselves.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Wednesday, 3 November 2010

Is America The New Weimar?

Tuesday, 2 November 2010

The Chinese Keynesians

Sunday, 31 October 2010

Mr Bernanke’s Gamble

Events are unfolding that could lead us interesting times. The US corollary to Mr Osborne’s gamble is a gamble by Mr Bernanke – of equal intent, but with far greater magnitude – to kick start the American economy. This is something of an untried experiment, to combine fiscal tightening with monetary easing in order to fine tune the economy, and we have yet to see how well it will go. There is a real danger of diminishing returns (QE2 will yield less stimulus per £ or $ injected) that may render the medicine unhelpful. More fiscal stimulus would do the trick, but there is little appetite for this at present.

The fears of QE2 inducing a bout of inflation still seem to be far fetched. That could be an effect, but the output gap is absolutely huge in the US. Economists might talk about the ‘output gap’ in an impersonal way, but in the US, ‘output gap’ means people living in cars, people without healthcare, people who have to give up their education. Perhaps economists, who are in no position to talk about moral hazard, ought to give some thought to the consequences of their trade a bit more?

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

America's economy: Not by monetary policy alone | The Economist

Friday, 29 October 2010

Anyone For Tea?

The forthcoming mid-term elections have taken on the hue of a referendum on the popularity of President Obama. A mere two years ago, the President was billed as a new and dynamic political force in America. His rally cry was ‘Hope’, his exhortation ‘Yes, we can.’ And yet, the programme seems to have come off the boil. ‘Hope’ now turns out to be ‘Hype’ and, in an unguarded moment on a TV show recently, he now says ‘Yes, we can. But, …’ If the polls are anywhere near to being correct, the President’s party is facing a substantial defeat in the voting next week. As an outsider looking in, I am interested in why America has fallen out of love with Obama? Why is it that his opponents are so hostile towards him? What exactly is driving the extreme views of the Tea Party opponents to the President?

I guess that the single word answer is ‘recession’. America is experiencing a recession that is at the worse end of the OECD experience, and this is exposing some of the fractures within American society. However, we like to take a longer view of these fractures in seeking an explanation.

According to Edward Luce of the FT, “the annual incomes of the bottom 90 per cent of US families have been essentially flat since 1973 – having risen by only 10 per cent in real terms over the past 37 years”. This is quite an interesting statistic because it also explains so much. If income has flatlined in this period, and living standards have been increasing, then how has the American Dream been paid for? By an increase in household debt. It would appear that American consumers have been borrowing to improve their living standards. A good part of this increase in debt was underwritten by a boom in the housing market, as households used their mortgages as credit cards.

Of course, there is nothing inherently unstable about this money-go-round until the music stops. Once that occurs, then everyone wants to ditch the parcel rather than being left with a dud asset. As the credit crunch – essentially a financial phenomenon – bled into the real economy, the resulting recession has had two important consequences. First, there is an acute shortage of credit to finance further expansion of consumer expenditure (more on this later), and second, there arises unemployment at sufficient volumes that the servicing of existing debt is called into question.

This is compounded by the composition of the borrowers. Many of those who have borrowed to finance their lifestyles are of the Boomer generation, and one thing that characterises the Boomers is their deep sense of entitlement. We now have a situation where a generational cohort, who are accustomed to being treated like spoilt children, have had their toys taken away from them. They are angry. They are angry enough to form Tea Party groups. They are angry enough to call into question whether their own President is American. They are angry enough to give credence to extremists such as Glenn Beck. And they may just be angry enough to vote into office someone like Christine O’Donnell, who is manifestly unfit for office.

It could be quite easy for Europeans to become smug over the discomfort of America. However, just an element of deep thought stops this train of thought. It is the angry, white, lower middle class who are giving electoral backing to the Neo-Nazi parties in the UK. It is the respectable burghers who are giving electoral support to the anti-Islamic parties in the Netherlands. It is the middle class establishment who are behind the hounding of the Roma in France and Italy. There are angry middle class voters across the developed world at the moment.

This is likely to be a feature of our near future. If recovery is sluggish (the best case scenario) or if recession makes a re-appearance (the worst case scenario), it is unlikely that middle class household balance sheets will be repaired quickly. In the past, the world has waited for American households to start borrowing to finance their consumption, thus kick-starting the world economy. This is unlikely to happen for some time – American households are simply too maxed out. This suggests that middle class anger will remain for some time to come, which will make our politics just a little more xenophobic and our economies just a little less globalised.

We call this trend the ‘New Nationalism’.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

FT.com / Reportage - The crisis of middle-class America

On the Way Down: The Erosion of America's Middle Class - SPIEGEL ONLINE

BBC News - Number of Americans living in poverty 'increases by 4m'

Glenn Beck Leads Religious Rally at Lincoln Memorial - NYTimes.com

BBC News - Profile: Christine O'Donnell, Delaware Senate candidate

Growing Number of Americans Say Obama is a Muslim: Pew Research Center

Thursday, 28 October 2010

Ageing Europe

BBC News - Q&A: French strikes over pension reforms

Wednesday, 27 October 2010

Ever Increasing Union

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Bush III

BBC News - Canadian militant pleads guilty at Guantanamo tribunal

Monday, 25 October 2010

Productivity–vs- Competency

BBC News - Tetraplegic man's life support 'turned off by mistake'

Sunday, 24 October 2010

Globalisation Fast Tracked

Saturday, 23 October 2010

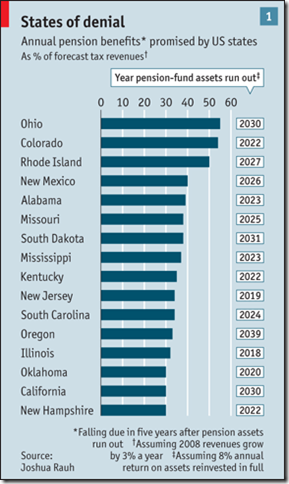

When The Well Runs Dry

Of course, the bond markets will intervene well before this scenario occurs, but it does suggest that, towards the end of this decade, a crisis in State funding – along the lines of the crisis in the Eurozone – will befall the Dollar.

Ooops … it looks as if we can’t afford to retire!

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Friday, 22 October 2010

Mr Osborne’s Gamble

The news in the UK this week has been dominated by the Comprehensive Spending Review. This is the first attempt within the OECD to match financial planning with the rhetoric of deficit reduction. There is much that still has to come out of the review, but the broad shape of the deficit reduction can now be discerned.

To start with, there has been the decision to place a far greater reliance upon cuts in public spending than tax increases to eliminate the deficit. In measures previously announced, about £20 bn tax increases will start to have an effect in the current fiscal year. Of those, the greater proportion will be increases in taxes on consumption rather than on income and savings. A ratio of 4:1 (£4 in spending cuts for every additional £1 raised in taxes) is a bit unusual. Normally we would expect a ratio of 3:1.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer (our quaint title for our Finance Minister) announced about £80 bn in spending cuts. Whilst all departments will face some degree of financial restraint, the bulk of the spending reductions have been directed to the welfare budget (the old and the poor) and spending on local public services (social care, local education, the police, libraries, and climate resilience). Leaving on one side whether the politics of these makes sense, the objective of the cuts is to enhance our future prosperity and the more pressing question is whether or not the policy will work.

In a paper delivered to the Post Keynesian Study Group at the University of Cambridge, Victoria Chick presented evidence to suggest that for every 1% reduction of government expenditure as a percentage of GDP, there would be a corresponding rise of 0.6% in the level of public debt as a percentage of GDP. The mechanism by which this happens is quite obvious. As government expenditure falls, employment levels fall (over 80% of public expenditure is on salaries). As employment levels fall, income tax receipts fall and unemployment benefit payments increase, leading to an increase in the deficit. We can see why the government’s own Office for Budget Responsibility have warned that there is a 40% chance that more deficit reduction measures will be needed in the near future.

Of course, this begs the question of how the deficit reduction plan is supposed to work. The workings all hinge around expectations. If, it is supposed, the public were to believe that the policy would work, and that they see as credible a permanent reduction in taxes, then they would increase their consumption expenditures accordingly. The private sector – having been crowded out by the public sector – would then increase to satisfy this demand, triggering further growth. The key to this plan is an improvement in household and business confidence. Unfortunately, recent evidence points in the opposite direction. Businesses are confident that their sales will fall as public sector workers are made redundant. Households are confident that a better use of their resources is to build their precautionary balances, and so the savings rate rises.

And this is Mr Osborne’s Gamble. He has bet that the recovery in household and business confidence will trigger growth at a rate to offset the deflationary impact of public sector redundancies. The Chancellor estimated that just under half a million public employees would be displaced by 2014-15. However, there will also be a knock on effect in the private sector. The OBR estimates that a further half million private sector jobs will be lost as a direct result of the spending reductions (much of the public sector is currently delivered by the private sector). If we add to that the half million jobs lost since the onset of recession, for the plan to work, the private sector will need to create at least one and a half million jobs within four years. The Treasury calculates that the private sector has the capacity to create two million jobs in this time frame. However, having the capacity to create jobs is one thing and actually creating them is another.

We shall see how Mr Osborne’s Gamble plays out. If he is right, then we will have a muted recovery for half a decade. If he is wrong, we may well have a muted recovery for at least a decade. Either way, when I look at scenarios with a ten year horizon, I will need to look for the assumptions about Mr Osborne’s Gamble. This will take on a greater significance with an international dimension when it is recalled that the UK is the first actor in OECD to detail the cuts. As other economies in Europe follow suit, so the process will gather momentum internationally.

The position of the US is more interesting than usual. At present, the White House is disinclined towards fiscal tightening. However, if the polls are correct and the Tea Party candidates rise to prominence in the Mid-Term Elections, then deficit reduction plans will take a more central role in the US. However, that is a story best left for another week.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Thursday, 21 October 2010

QE2?

QE is also being used to fine tune the economy. I rather suapect this to be something of a blunt instrument. The policy of fiscal tightening and monetary loosening is novel, but I do fear that the tightening might be overdone. For example, for Mr Osborne's plans to work, the private sector needs to generate something like a million jobs in the next four years in order to soak up that half million recently unemployed during the recession and the half million displaced public sector workers created in the recent spending review. This seems like a tall order at a time when GDP growth will be, at best, muted. A million jobs over the decade might be a more reasonable prospect.

Which brings us to Faisal Islam. His article for Prospect Magazine rather reflects conventional thinking. Stuck in the grip of a neo-classical base for his economics, he fails to grasp the key points of QE. In my view, this reflects the failure of economics more than anything else. Perhaps what we need is a new economics?

The Great Money Mystery – Prospect Magazine « Prospect Magazine

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Wednesday, 20 October 2010

US inquiry into China rare earth shipments

BBC News - US inquiry into China rare earth shipments

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Tuesday, 10 August 2010

Why Go To Boston?

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Thursday, 29 July 2010

Plate Tectonics In The North Atlantic

Saturday, 24 July 2010

Capitalism 4.0

The main thesis of the book is that something substantial has occurred in the recent financial crisis. We call it ‘The End Of The Washington Consensus’. The timing of this event varies between commentators. Those in the US date it at the collapse of Lehman Brothers, those in the UK date it from the nationalisation of Northern Rock. Either way, from that point onwards, things would be different.

What we do not know is how they will be different, and this is the contribution of the book. Mr Kaletsky takes a much longer view of the economy and starts to speculate about what comes next, which is exactly what we, as futurists, have been doing for the past couple of years. This is why we commend the book. It is not a map of the future, but it does serve as a guide into some fairly uncharted territory. If you are of the opinion that ‘back to business as usual’ is not an option, then this book is a good starting point for you.

Monday, 24 May 2010

Advice To My Children

“If you were advising your twenty-something children about investing in a pension, where would you advise them to invest?”

This is the conundrum that greeted me as I attended a Long Finance Roundtable recently (see http://www.zyen.com/long-finance.html). It is, actually, a really interesting question because it forces us to look again at many of our beliefs about the long term. I have been thinking about how to answer the question for a while now and I am not sure that I have a definitive answer. What we can do is start to examine some of the parameters.

Two key questions around this issue are: for how long will your retirement fund have to support you? And, how long do you think that you will save for your retirement? The first question gets at our attitudes towards how long we think that we will live. This is a delicate balance. One the one hand, life expectations are increasing and my daughters (both born in the 1990s) could reasonably expect to see a turn of the century twice – once at the beginning of their lives (the year 2000) and once towards the end of their lives (at the year 2100). On the other hand, there is the possibility of a long term event, such as climate change, significantly reducing life expectations later in this century. There is a great deal of uncertainty about our prospective life spans.

The second question looks at our attitudes towards work, our ideas of career, and the notion that, towards the end of our working lives, we can expect a period of rest. Our traditional view towards work and retirement stems from an industrial view of the workplace. If the knowledge economy establishes itself for our heirs, then one can question if ‘retirement’ is that desirable in the first place. The second question is not independent from the first, because, if we only partially accept the concept of retirement, then the retirement fund will have less strain placed upon it during our sunset years.

When first considering the problem, we are naturally led to start thinking of asset classes (stocks, bonds, property, and so on). However, this is a mistake. Our first focus ought to be on returns, and, from there, we should move on to asset classes. If we do this, then our first thoughts naturally go towards those investments that yield the greatest returns. I am of the opinion that we too often neglect our human capital, and that this is exactly the type of question in which it ought to be considered. Investment in our own education has to be the first port of call. Of course, our education is a wasting asset in that our knowledge will become obsolescent with time – some would say that the rate of obsolescence is increasing – so that, in order to stay current, we need to invest in life long learning.

Beyond that lies the social capital that we can access. Investing in our family and friends, over the course of a life time, will pay dividends many times over. We can enhance these returns by investing in our social networks. Interestingly enough, this investment is primarily non-financial. It is temporal. We need to make time for our family and friends to develop our stock of social capital. In recent years, however, I have been involved in a number of attempts to place a financial valuation upon the social networks embodied within an organisation. I see this as an attempt, in the Knowledge Economy, to leverage the valuation of what really creates financial value – our ‘know how’.

At this point we start to get into the world of financial assets. There is a long discussion about whether financial instruments are better stores of wealth than tangible assets such as property. Much depends upon how well you understand how the different classes of assets work, which basis periods you are comparing, and what else is happening in the wider world when the comparisons are made. Personally, I take the view that a portfolio ought to be balanced with a bit of all of the main investment classes. However, I accept that many people disagree with me.

To come back to the original problem, I think that I would be inclined to advise my children to invest in their own human capital as a matter of priority. Beyond that, the next investment priority would be to invest in their social capital – building strong ties with family and friends. Finally, to start building a stash of financial assets. This last task will be that much easier if they have done the first two tasks effectively.

I am reminded of an old adage – remember your friends on the way up because you will need them on the way down!

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Wednesday, 28 April 2010

A Bit Of Clarity

We have received a number of requests to clarify and expand upon a point made in our last update. In it we said that “the US stock of debt has a half life of just over 4 years and a coupon of just under 6%, which suggests a very pressing issue for the 2016 US Presidential Election”. We have been asked to explain exactly what that means and what chain of events might be triggered out to 2016.

To understand this, we need to start with the nature of public sector debt. Although an individual loan instrument has a fixed term, it would be wrong to think of public sector debt as fixed in nature. Because treasuries around the world issue a number of instruments with varying maturity dates at different times, public sector debt is a lot more fluid than we might think it to be. In many cases, the debt is revolving, which means that new debt is issued to repay old debt as it falls due. This is quite normal. Public sector debt is less like a mortgage – a single loan of fixed term used to purchase a big ticket item – than it is an overdraft – a series of lending and repayment events used to smooth out cash flow fluctuations.

At any one point in time, the US Treasury will be issuing new debt instruments, of varying repayment maturities, and either spending that money on fiscal expenditures or using that money to repay old debt. The balance between debt repayment and making fiscal expenditures is largely determined by the size of the fiscal deficit – the extent to which taxes are insufficient to meet expenditure obligations. As deficits grow there is greater pressure to delay the repayment of debt and to allow the total amount owed to increase.

However, the total amount owed cannot increase without check for two reasons. First, because the total debt is a collection of loans for fixed terms, the time profile may well be very uneven. If so, then there comes a point where the total amount borrowed (i.e. the debt repayment that cannot be avoided plus the size of the fiscal deficit) exceeds the willingness of the bond markets to lend to the government. This brings in the second constraint. As we are currently witnessing for Greece, the willingness of the bond markets to lend to a government is partly determined by it’s credit rating and partly determined by the price at which the government is prepared to borrow. These two reasons are why the time profile of the debt and its coupon (i.e. price) are very important.

We measure the time profile of the debt in terms of its half life. This is the period of time in which 50% of the total amount owed falls due for recycling. A short half life combined with a large fiscal deficit implies that the government has a real problem in its immediate future, which will only be solved by drastic reductions in its fiscal deficit (this means emergency and severe spending cuts followed by steep tax increases, as in the case of Ireland) or by the cost of borrowing rising disproportionately (as has happened with Greece, along with the consequential downgrading of Greek debt by the credit ratings agencies). In both cases, the remedial action is likely to be sufficient to trigger a major political crisis.

Bearing this in mind, it is worth using this framework in the case of the USA. The USA has a very short half life for its debt. At 4 years, it is one of the shortest repayment profiles in the OECD. The American fiscal deficit (both Federal and State deficits combined, if we are to compare like with like) is relatively large (11.1% of GDP in 2010 according to the EIU) compared to other OECD nations. In the absence of a strategy to alter this state of affairs, this would suggest that a refinancing crisis could emerge somewhere towards the middle of this decade. The crisis is likely to occur after the 2012 Presidential Election, but could well become a major factor in the 2016 Presidential Election.

There are two aspects to this problem – the savings glut in the global economy and the savings shortage in the US economy. One solution would be for the US economy to save more. To date, the household sector in America has been reluctant to save. Experience elsewhere in the world suggests that if the household sector will not save, then the public sector must do it for them through higher taxation. There is every expectation that this will become a pressing issue in the 2016 Presidential Election, simply because resolving the question of the fiscal deficit is likely to become very pressing.

Of course, raising taxes is not a popular policy, particularly in America, but then, as we said before, the remedial action is likely to be sufficient to trigger a major political crisis.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Friday, 26 March 2010

A Tale Of A Jig-Saw

It sometimes helps to view the future as a very large and very complex jig-saw puzzle where, in the present, we have most of the pieces to the jig-saw. The skill of the futurist is to fit those pieces together in a way that allows us to view the future usefully. This process is often made more difficult by the ambiguities of the final result – a blue jig-saw piece could be part of a sky scape, or it could be part of a sea view, or it could even be part of a more obtuse mountain scene – and the fact that the future will also make up its own pieces as we go along. However, despite these problems, sometimes a group of pieces just fall into place together at more or less the same time to reveal something quite useful about the future. Just such an event has happened recently.

As our readers will be aware, we have been tracking the course of UK unemployment for the past year. About fifteen months ago, many commentators expressed the fear that UK unemployment would rise to 3 million by the end of 2009. In the autumn of 2008, we felt that unemployment would rise to 2.25 million. As the full impact of the recession started to be felt, we revised that forecast up to 2.5 million. The difference in the forecasting can be attributed to different modelling techniques. In the event, unemployment reached 2.46 million in December. We were interested in this because the out-turn of actual unemployment is quite likely to shape the course of the UK economy for the next decade – it is one of those things that may have a small impact in the present, but with large consequences in the future.

Moving the story forward, if unemployment is not as bad as forecast (remember, the forecast error is 100% – a rise of 1 million was forecast whereas unemployment only rose by 0.5 million), then all other subsequent forecasts will be wrong as well. The impact of the automatic stabilisers (welfare benefit payments increasing and tax receipts falling as unemployment rises) will be lessened. It transpired this week that the lesser impact was to reduce PSBR by £11 billion this year, with a consequential impact of £14 billion next year. Of course, this is money that the government doesn’t have, which means that the stock of debt will be smaller by £25 billion over the next two years.

In turn, this makes the UK debt look just a bit more manageable. The half life of the UK stock of debt (the period of time by which 50% of the stock of debt needs to be repaid or recycled) is 14 years with a coupon of just over 4%. This is one of the better profiles in the OECD (by way of comparison, the US stock of debt has a half life of just over 4 years and a coupon of just under 6%, which suggests a very pressing issue for the 2016 US Presidential Election). We have already pointed to the impact of inflation in reducing the real value of the debt. If the Bank of England hits it’s 2% inflation target on average to 2024 (when the half life falls due), then £1 borrowed in 2010 will only take £0.75 to repay in real terms in 2024. Added to that, if we also factor in the possibility of inflationary drift in the taxation system, then the impact of inflation on the debt will be to reduce the debt burden even further. It is no surprise to us that the Chancellor neglected to increase the tax thresholds by the rate of inflation in the recent Budget – it is a sneaky 3.5% tax rise in real terms that took the Opposition days to recognise.

We were also told, for the first time, in the recent Budget that the Government intends to sell it’s bailout holding in the UK banking sector, when conditions allows, to repay some of the UK debt. Ignoring the question of the wisdom of this approach – the Government currently receives interest and fees of about 12% on every £1 used to bail out the banks, which explains why the banks are very keen to repay this money – the issue arises of how much they might receive. Our previous estimate of between £350 billion and £400 billion in a time frame of 2018 still looks good to us. All of this suggests that the plan to pay down the bulk of the stock of debt by the second half of the decade looks to be quite credible if about a third is covered by bailout repayments and about a third by the impact of inflation.

And yet the markets don’t quite believe it. UK sovereign debt currently trades at a premium of 120 basis points (that’s 1.2% in ordinary language), despite the Triple A rating for the UK. This isn’t sustainable. Other Triple A economies (e.g. France and Germany) trade at a premium of 50 to 60 basis points. Looking at it another way, the UK debt is trading at about the same premium as Greece despite the clear differences between the two economies. There is talk about the UK being downgraded from Triple A. If that were to happen, then we would see that as a buying opportunity because the UK would be undervalued at that point. If, as is more likely, that doesn’t happen, then we can expect the premium to fall back to Triple A levels.

In many ways, this suggests that Sterling is undervalued, in a long term sense. It may be quite deliberately kept so because the low value of the Pound against the Euro and US Dollar is quite handy for UK exporters to the Eurozone, the US, and those parts of Asia that peg their currencies to the US Dollar (read: ‘China’ here). The UK is exporting – some might say ‘dumping’ - its excess supply overseas by, as a matter of policy, keeping low the cost of British exports in overseas currency terms. A low currency does contain the danger of inflation, but this is held in check at the moment by the output gap – the difference between actual GDP and potential GDP.

The size of the output gap is difficult to measure because potential GDP is a rather speculative concept and actual GDP in the most recent past is subject to significant revision. However, despite this, we are comfortable with a view that the output gap is between 5% and 10%, which suggests that Sterling could appreciate, over the course of this decade, by a similar amount. And that really brings us back to the starting point. We are of the view that the doom and gloom in the UK is overdone. There are areas and sectors which have been very badly hit by the recession, but there are also sectors and regions that are very much untouched. It is worth remembering that the pain has not been spread evenly. However, the prospects for the next decade look quite good – a decade of slow recovery, but where the UK is more likely to fare better than our comparable partners in Europe.

Of course, there is still scope for policy blunders, both at home and abroad, which could make things worse. Let us hope that we get the political masters that we deserve!

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Wednesday, 13 January 2010

The Rise Of The China-sceptic.

Every now and then, a novel idea enters the public domain. At first, that idea sounds a bit off-beat – almost revolutionary. Eventually the idea is taken up by more and more people so that it manages to reach the mainstream. Beyond that, if the idea gains traction, it becomes part of a new conventional wisdom. Once there, anyone who questions the idea is seen as something of a crank. The ideas behind the rise of China fall into this path. Originally, at the turn of the century, the notion that China would be a rising super-power was seen as fanciful. The then conventional wisdom of the Washington Consensus had no place for China.

Goldman Sachs questioned that conventional wisdom when they developed the notion of the BRIC economies. Over the course of the decade, as the BRIC economies grew relative to the OECD economies, so the notion took hold. It has now reached the point where it has become the conventional wisdom. I attend a number of futurist meetings each year and at each one I am greeted by the mantra that China will have the largest economy in the world by the 2020s. Personally, I very much doubt this.

My cause for scepticism is threefold. First, there is the question of demographics. The ‘One Child Policy’ has served China well to date but, at some point in the coming decade, it will go into reverse, giving rise to a sharply growing dependency ratio (the ratio of working population to non-working population). Unless China experiences a very high level of labour productivity growth to compensate, as the size of the working population falls, so GDP growth will come off the boil. The decade may witness the reduction of GDP growth in China to the 5% to 8% band.

At this point the second cause for scepticism assumes importance. As time goes on, the law of large numbers will start to act as a constraining factor to the Chinese economy. High growth rates are easier to achieve when the economy is relatively small, but much harder for a large economy to maintain. This is why the growth rates of the BRIC economies are much higher than those of the OECD economies. For example, the raw materials that are needed to run the Chinese economy at it’s present levels have caused most markets for raw materials to tighten. At some point during the next decade or two the demand for those raw materials is likely to exceed the capacity to supply them, acting as a limiting factor to further growth.

Third, to close the feedback loop, China has a very high savings ratio – mainly in response to the absence of a welfare safety net, as most Europeans would understand it. The private sector is saving through bank deposits, which are, in turn, being lent to fuel property and stock market bubbles. Usually, the creation of such bubbles suggests a lack of productive investment opportunities and foreshadows a financial crisis as and when those bubbles burst. Any slight disruption to the Chinese economy could lead savers to ask for their money back, precipitating something of a financial crisis. Given that the Government of China has deposited its surplus funds in US Treasury Bills, there are grounds to suspect that financial contagion could spread quite quickly. If that were to happen, then the overtly nationalistic policy of the Chinese Government could well hamper a co-ordinated global monetary response to contain the contagion.

This is not to say that we are predicting the financial collapse of China. What we are saying is that the development of the Chinese economy is a lot more fragile than it appears, and that an uncritical view of the conventional wisdom does not encourage a balanced review of future prospects. It is correct for futurists to point to a trend of China becoming a greater economic force in the world. However, good futurists would also point out that for every trend, there is also a an important counter-trend that could well turn into a new conventional wisdom. Over the past few months, I have noticed the growth in the China-sceptics. More and more articles that question the conventional wisdom are being published (I have included the links to a couple below), which suggests that we might be seeing the start of a turning point.

Only time will tell if the case for China has been over-made. However, given its importance, I think that it is an issue to which we will return from time to time.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Contrarian Investor Sees Economic Crash in China (New York Times 07/01/2010)

Think Again: Asia's Rise (Foreign Policy, July 2009)

Tuesday, 5 January 2010

Scarcity Bites – A Decade Too Soon!

The twin concepts of scarcity and plenty describe a complex relationship between what we have and what we need to have if we are to do everything that we want to do. In many respects, one aspect of the future that will enter into our consciousness in the very near future is that of scarcity. In simple terms, scarcity suggests that the supply of a resource is not sufficient to satisfy its demand. As the global population increases, and as that population has expectations of higher living standards, so the demand for resources will rise. However, as we start to feel the finite nature of our resource endowments, scarcities will start to emerge. This is the underpinning of much thinking on the issue of ‘Peak Oil’.

It is our contention that energy is not the only resource that will be scarce in the immediate future. We envisage scarcities of food, water, and a whole variety of minerals that are crucial to the operation of a modern economy. Our thinking so far has focussed on the 2020s as the decade in which scarcity starts to be felt (we call it ‘Scarcity Bites’), but recent events have drawn our attention to a much earlier manifestation.

A recent article in The Independent (see below for link), has drawn our attention to the case of the Rare Earth Elements (REEs), a group of 17 rare metals that are essential to the manufactures of the modern economy which are in a situation of scarcity (demand outstrips supply). The picture is further complicated by China being the main source of the REEs (it supplies over 95% of the world total of REEs) and following a policy of restricting their export. This conjures up some fascinating possibilities for the future.

The onset of scarcity is likely to lead to a large spike in the price of the scarce resource. In many respects this has already happened for REEs. The spike in price will have three important implications:

- Alternative sources of the scarce resource that have been abandoned as financially unviable will be reappraised, some of which will now be viable, and will then return into production.

- The high cost of the scarce resource will be sufficient to stimulate research into viable (i.e. less costly) substitutes for the scarce resource, some of which will be viable and help satisfy the demand for that resource.

- The high cost of the scarce resource will encourage users of the resource to be more parsimonious in their use of the resource. This will act to assist the conservation of the resource to elongate its supply.

As the demand and supply for the resource become tempered, the price will fall back from its previous high to a new, more stable, price. This is a standard analysis using Marshallian Time Periods.

The monopoly of production in China is a complicating factor. The production of the REEs has no value to China per se. Their importance lies in being a constituent part of a number of key manufactures. In many respects it matters little outside of China if the REEs are exported in mineral form or in the form of embodied manufactures. China has enriched itself on being the global source of cheap manufactures.

This only works as long as the manufactures are cheap. However, the embodied REEs, as a small constituent cost in the manufacturing process, can increase in price substantially before they have an impact on the overall price of the manufactures. For example, suppose that we have a good that uses REEs, costs £100 to manufacture, and the REEs represent 1% of the manufacturing cost. If the REEs were to treble in price, the manufactured cost would only rise to £102, a 2% increase in the cost of the manufacture after a 300% increase in the cost of the REEs.

Economic theory would suggest that we ought not to worry too much about the scarcity of REEs starting to bite. As a small component cost in the overall manufacturing cost, the increase in their prices is unlikely to have a major inflationary impact. It is likely to stimulate production elsewhere in the world (Australia and Greenland are two contenders), thus lessening the monopoly of China. Viable alternatives to REEs will become more attractive, and the relatively high cost ought to make us conserve the stocks that we already have. However, this is a case of scarcity becoming evident a decade sooner than we thought that it might. Either way, it should be an interesting case study for the onset of more serious scarcities (Food, Energy, Water) later in the century.

It appeals to that part of me that is a small boy with a beetle in a jam jar!

The issues covered in this post are dealt with at greater length in our forthcoming book “The Age Of Scarcity 2010-50”.

© The European Futures Observatory 2010

Rare Earth Elements: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/precious-metals-that-could-save-the-planet-1855394.html

China and REEs: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/concern-as-china-clamps-down-on-rare-earth-exports-1855387.html